- Wes Anderson Biography

- Wes Anderson Style

- Wes Anderson Influences

- Wes Anderson Lessons

- Wes Anderson & Peter Pan

- Wes Anderson Scripts

- Wes Anderson Characters

- Wes Anderson Directing

- Wes Anderson Cinematography

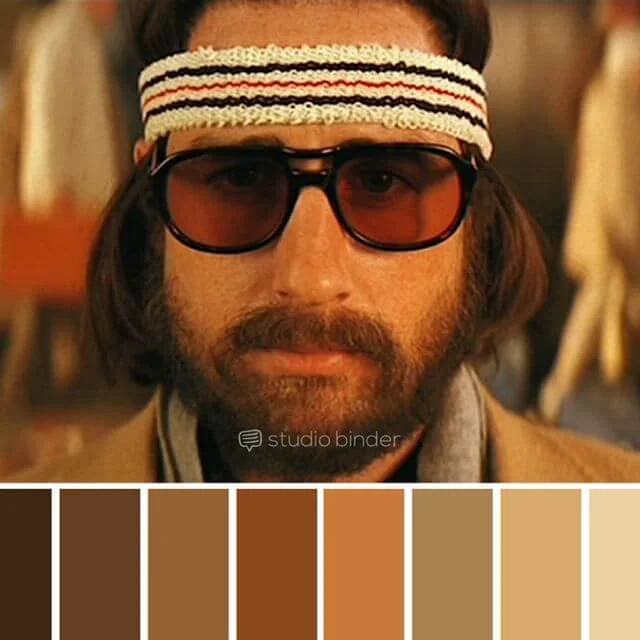

- Wes Anderson Color Palettes

- Wes Anderson Costumes

- Wes Anderson Font

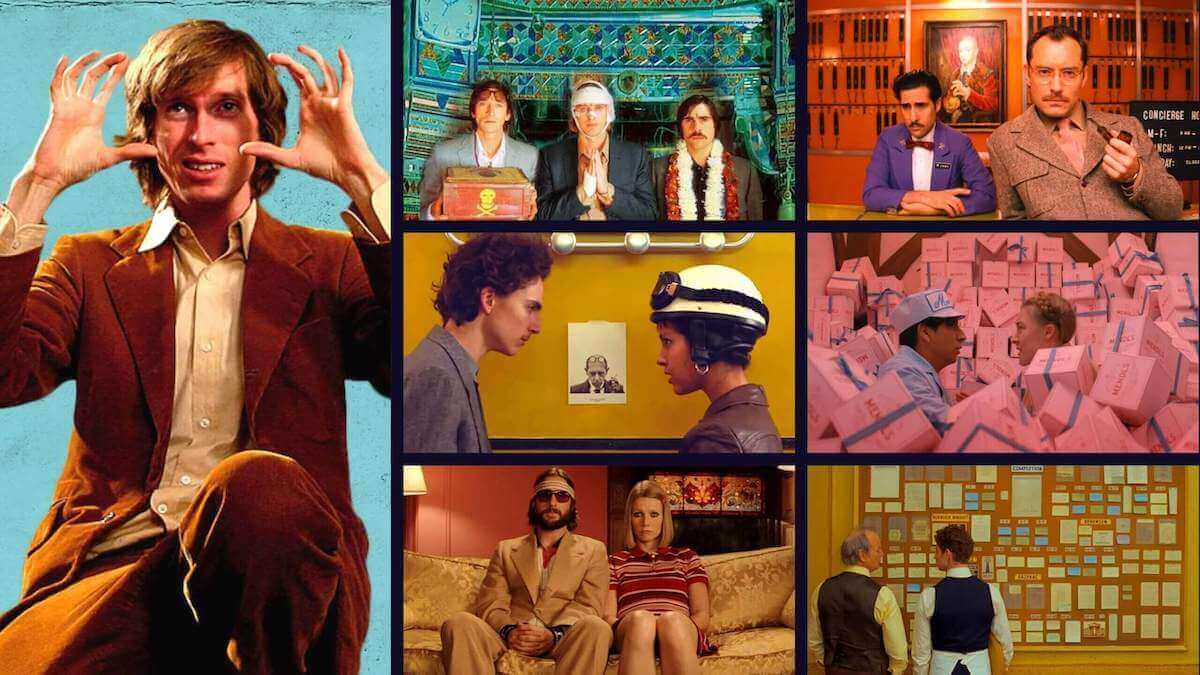

- List of Wes Anderson Movies

- Best Wes Anderson Movies

- Wes Anderson Awards

Wes Anderson Film Style

THE Wes Anderson Aesthetic

WES ANDERSON STYLE

Wes Anderson Biography

Wes Anderson grew up in Houston, Texas. He is the middle child of three boys. His parents divorced when he was eight years old.

He attended St. James Preparatory high school before he moved to Austin, where he attended the University of Texas and graduated with a degree in philosophy.

He made a short film, Bottle Rocket, which screened at Sundance in 1994, where it received little recognition by anyone other than producer Polly Platt. She later showed the film to Jim Brooks, and from there.

Wes Anderson’s career began.

Wes Anderson Style in Bottle Rocket • Subscribe on YouTube

WES ANDERSON LOOK

What is the Wes Anderson Style?

Wes Anderson’s style can be summed up as this:

Wes Anderson is the most direct director in popular cinema today, but his films are simultaneously idiosyncratic and relentlessly detailed.

Laced throughout his films are nuanced production design elements and visual gags, but executed in such a deliberate manner that the viewer always 'catches' these little easter eggs that inform our mood.

- Knows what he wants them to know.

- Sees what he wants them to see.

- Feels what he wants them to feel.

The Wes Anderson aesthetic is much more deliberate. It seems simple, but it's actually complex. The viewer gets to enjoy a sophisticated film that spoon-feeds information. His stories are undeniably fun, and he is one of the only working directors who can pull off massive tonal shifts.

Other directors will keep you in suspense by holding information back, and strategically distributing details when advantageous. The overall Wes Anderson aesthetic is rather charming, and this includes his blocking and staging, writing, and performances. His characters are often gracious, have respect for one another, and cherish past memories.

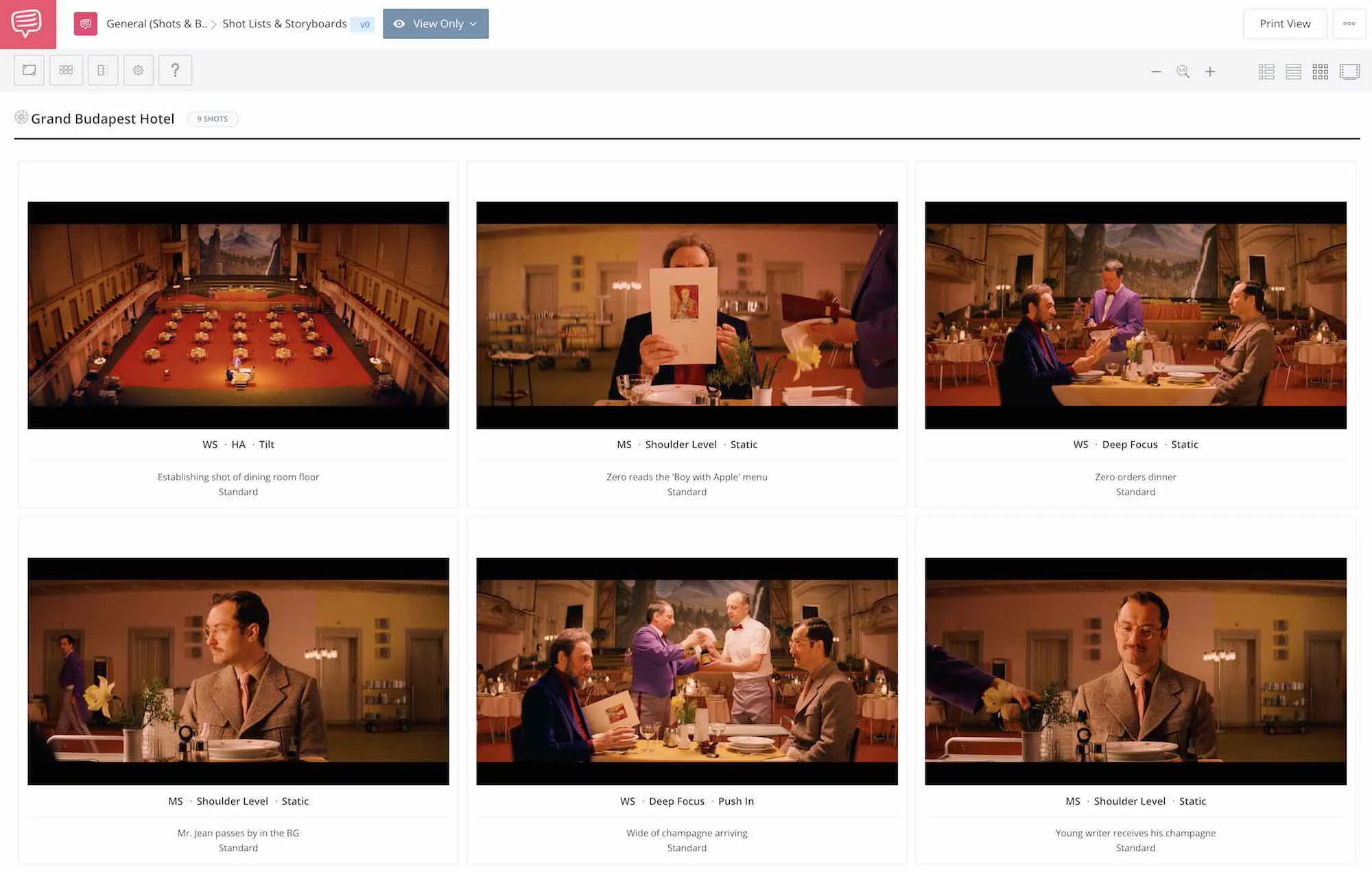

This is a scene where Zero (F. Murray Abraham) has dinner with the Young Writer (Jude Law). There is a love for tradition, and pride in one's craft, but something else in the scene is quite remarkable.

Wes Anderson Shot List • Made in StudioBinder

The scene has the trademark Wes Anderson symmetry and profile shots, with actors and props promptly entering and exiting the frame. Each action is cued by another action, much like the overall philosophy of the concierge and hotel staff. This extends to the dialogue as well.

There is a moment where M. Jean passes by in the background.

The Young Writer turns, just as he walks by, directing our eyes to the motion. Later in the scene, Zero mentions M. Jean's predecessor (M. Gustave) and as he does, we see M. Jean literally backtrack into the corner of the frame, just for a moment.

M. Jean backtrack in The Grand Budapest Hotel

It's subtle, and yet it's a great example of direct-directing. Its fast, and light, but strong and intentional. You might say, aggressively charming.

See if you notice any examples of direct-directing in these scenes:

Interview with Zero - The Grand Budapest Hotel

Wes Anderson willingly hands over information in a succinct manner. He doesn't try to trick you with his plot, and he has no intention of pulling the rug out from under you.

He is more interested in being clear than anything else.

Here is a great example of a video that mimics the Wes Anderson Style. Leave it to the team behind Family Guy to nail everything Andersonian.

Wes Anderson Style — Family Guy Style

The Wes Anderson style is Wes Anderson himself. A hard working, thoughtful human who is focused on his imagination. His visuals an extension of his own psychology. Anderson is those clothes, those Zissou Adidas, those record players. those memories.

Rather than portray himself predominantly through his characters, he finds a more sophisticated way to express his unique personality through his visuals.

This is where many other directors fall short with their auteurist spirit. Discerning film fans don’t get the feeling that Tarantino, Spielberg, or Nolan are, they themselves, visual representations of their films.

But you do get that feeling when you look at Wes Anderson.

You don’t have to like Wes Anderson films to appreciate the way he moves the camera, composes shots, and directs the actors. He makes robust, thoughtful films that use every department to the fullest degree.

Each of his more recent films could be described as a visually spectacular tour de force. This is because he pays “relentless attention to detail.” He directs your attention to what he wants, when he wants, and he is a master at making each image count through the use of cinema.

How Anderson Directs a Movie • Subscribe on YouTube

Wes Anderson films are predominantly made from scratch.

He can draw inspiration from books or other films, but he writes his own stories. His films hold a lot of information, feeling, and observation within a relatively simple narrative that is built by the artist that will eventually direct the picture.

Other elements of his films seem to be made from scratch as well, like his costumes and production design. While other filmmakers use real life locations or designs to create a cohesive world, Anderson seems to build his outright.

Even if he is using an established location, you get the feeling that the whole place was built for the film, and that is not done by accident.

You rarely see product placement — at least not for a real product or brand — or anything else that compromises the integrity of the film. Nothing violates the unique world of Anderson's personal creation — except maybe Adidas.

Related Posts

- Definitive Guide to Aspect Ratio →

- Creative Uses of the Low Angle Shot →

- Mise en Scene and How Wes Anderson Uses It →

WES ANDERSON FILM STYLE

Who influenced Wes Anderson?

Wes Anderson’s influences include Roman Polanski, Steven Spielberg, Alfred Hitchcock, Martin Scorsese, Waris Hussein, Ernst Lubitsch, Peter Bogdanovich, and French New Wave directors like François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard.

What's our source for that information? Just ask Wes:

I think the way I think about shooting scenes and staging scenes is influenced very much by Roman Polanski and by his films and the way he does that, which is very particular.

Also, watch his films closely.

There is a moment in The Grand Budapest Hotel that is an unabashed homage to a scene in the Alfred Hitchcock film Torn Curtain, as explained here by the Grand Budapest production designer Adam Stockhausen.

If you watch Torn Curtain and start where he’s walking out of the hotel and the women are scrubbing the floor, and Jeff Goldblum walking down the stairs with the women scrubbing the floor in Grand Budapest, it follows pretty exactly. It’s the most direct homage we’ve done. It’s exciting because you have this starting point that you then get to work into your locations and figure out how to match up the pieces.

This shows you just how much Anderson borrows from past filmmakers, and how he has a desire to retain some of those visuals and feeling he connected to as a young man.

Related Posts

- How to Write Better Dialogue →

- Short Films You Can Really Make →

- Make Your Blocking More Interesting →

WES ANDERSON TECHNIQUES

Lessons of the Wes Anderson style

The Wes Anderson film style is his own personal style, and he has gone to great lengths to cultivate a unique approach to cinema.

It is an amalgamation of books, films, experiences, and games that he created both as a child, and continues to create as an adult. Learning from Anderson is one of the most important things you can do as a filmmaker. Replicating his style is one of the more questionable things you can do as a filmmaker. If you let Wes Anderson influence you too much, you'll always be compared to him.

Even Wes Anderson and Quentin Tarantino knew that while they loved Godard, they couldn’t just rip off everything that made him unique. They studied why his style worked, and then blended it with all the other useful observations they made about film.

A filmmaker's visual style can, and almost always does, emulate those who have come before. But memorable filmmakers develop their own trademark techniques and styles to become an auteur.

Check out this video on production design to learn how:

Production design techniques to craft your own filmmaking style • Subscribe on YouTube

Wes Anderson felt that Bill Murray accepted his role in Rushmore because Anderson held his own during a discussion of the Kurosawa film, Red Beard.

Anderson had not seen the film, but he was confident enough in his artistic vision that one of the biggest movie stars in the world decided to come on as a supporting role after reading the script and having a phone conversation.

It was because Anderson had developed his own style, his own vision, and put it down on the page in a way that Murray says, he had never seen before in his long career as an actor. He had yet to make any of his famous stylized films with the pastel color palette or Adrien Brody, but Murray said “yes” to the young indie director from Austin.

Wes Anderson Stories

THE WORLD AND THE CHARACTERS

WES ANDERSON Film STORIES

Wes Anderson & Peter Pan Syndrome

Wes Anderson tells stories from the perspective of a 12-year-old boy. More specifically, he tells stories from his perspective as a 12-year-old. His films capture the essence of a board game or story book, and the world he builds in each film resembles a snapshot from his childhood.

Anderson's color palettes, costumes, set design, and technology all seem to create a world frozen in time somewhere in the early 1980s.

Audiences love Wes Anderson films for a multitude of reasons, some of which could be deemed "masculine." There is an undeniable sense that his films often are told from the perspective of a young man.

When you're 11 or 12 years old, you can get so swept up in a book that you start to believe that the fantasy is reality. I think when you have a giant crush when you're in fifth grade, it becomes your whole world. It's like being underwater; everything is different.

His films aren’t particularly “macho” when compared to high octane thrillers or shoot-em-away action flicks, but his main characters are predominantly straight(ish) men who have a sense of childish adventure that conflicts with their actual age.

They shirk responsibility to maintain some warped sense of independence, but they soon realize that they are stronger with others, that they are better off when they are happy, and that the very thing that tortures them also grants them their unique spirit.

Gunfight at The Grand Budapest Corral

Anderson proves that you can’t have one without the other. You can’t have the charm without the juvenile imagination. This recursive nature of Wes Anderson protagonists (arguably, we'll admit) doesn’t get old.

WES ANDERSON WRITING STYLE

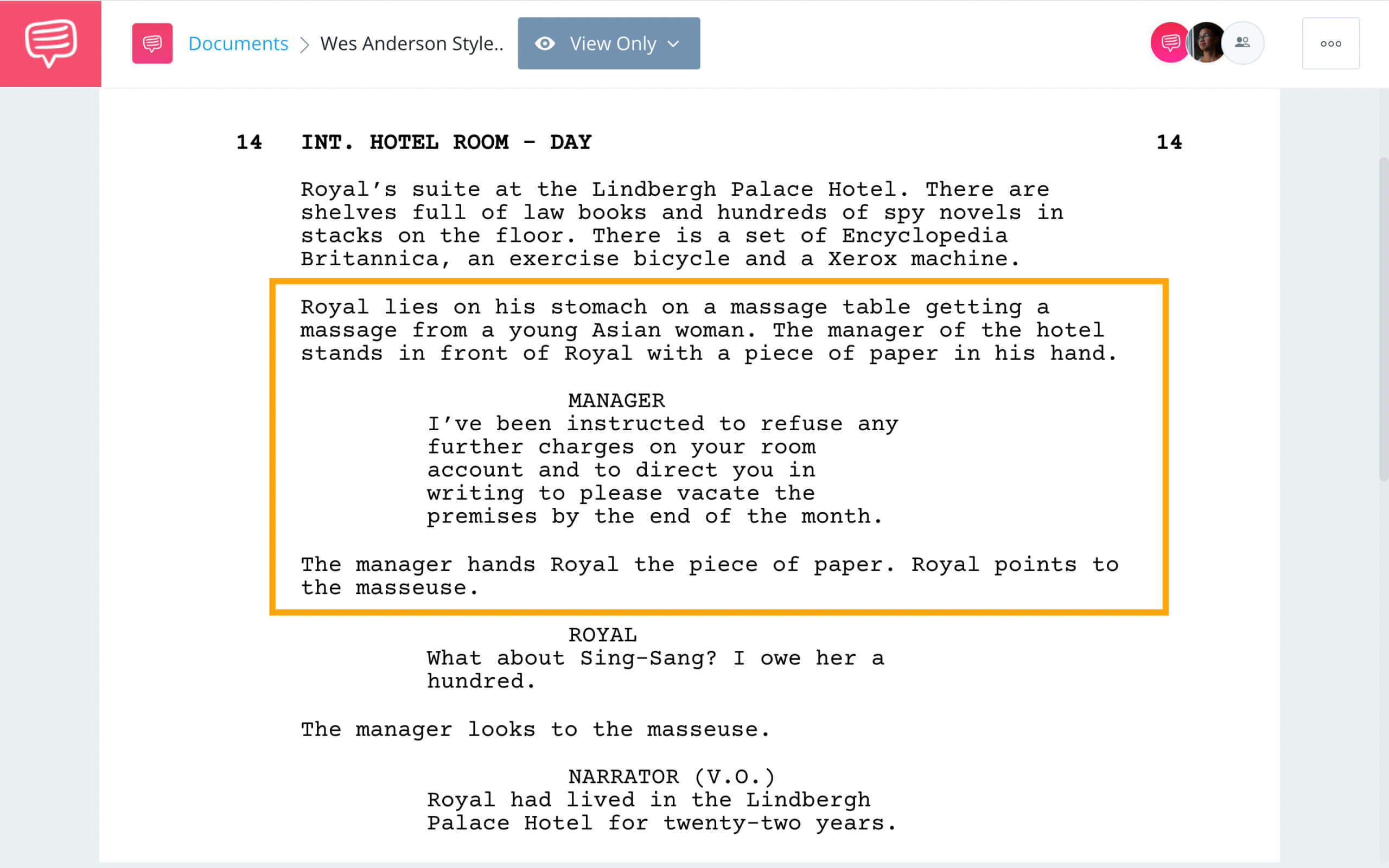

What makes a Wes Anderson script?

Wes Anderson scripts are completely finished when principal photography begins. He doesn’t limit his imagination for budget constraints. Anderson writes what he wants to write, and then finds a way to get it on film.

The action is precise. He knows exactly how he wants to play out each scene. Anderson will double down on expository information.

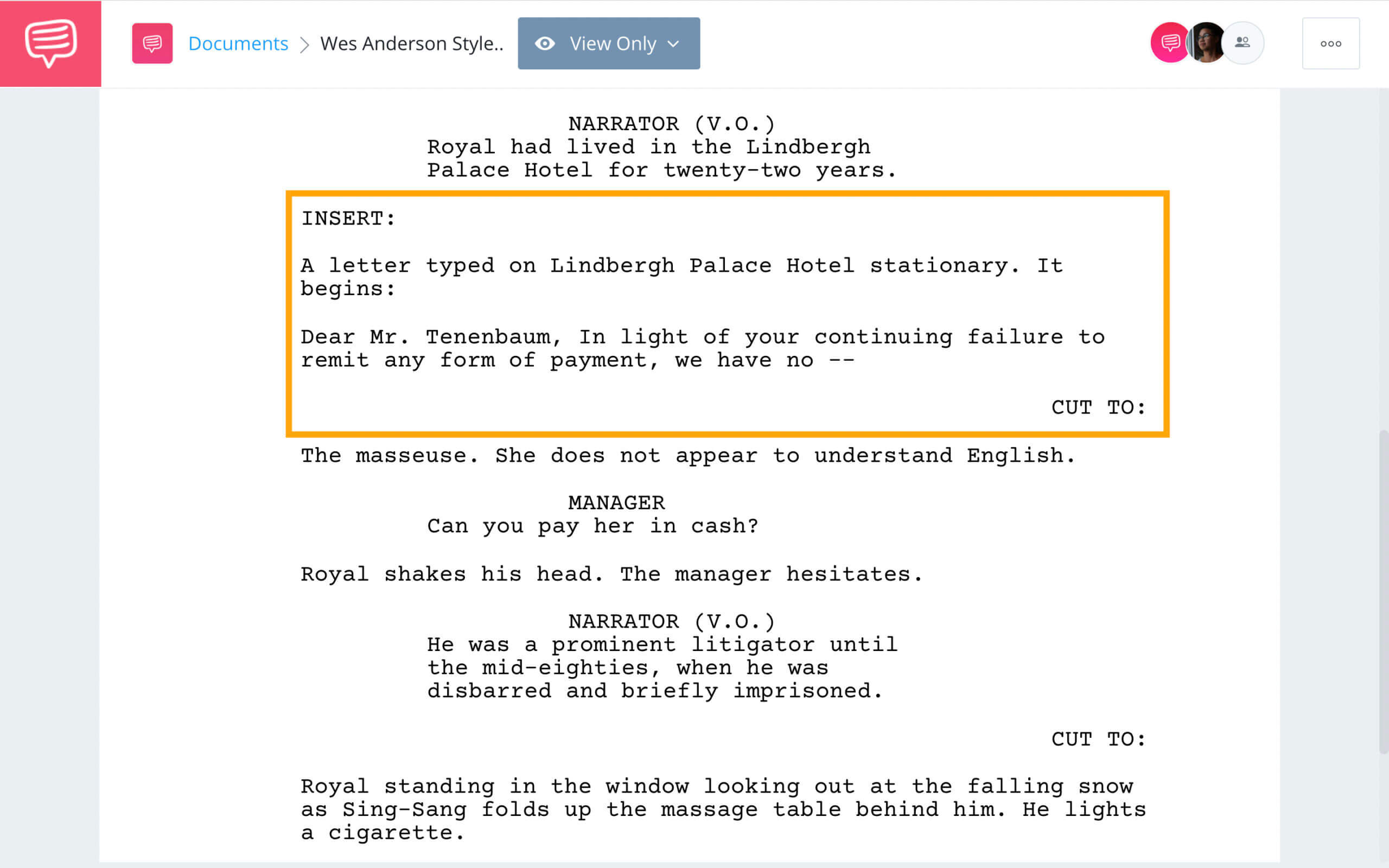

If a character receives a letter…Anderson will show you the letter.

His exposition is wonderful because it is so on-the-nose. Anderson has found a way to completely bypass the clunky presentation of essential information that so many other directors struggle with.

He drives home the information so that the viewer can’t miss it. The scene below takes place on page 13 of a 120 page script. Screenwriters know that this is roughly where you should have your inciting incident.

The Royal Tenenbaums Script

We have the necessary information told to us by the manager.

The Royal Tenenbaums Script

But then Anderson cuts to an insert shot of Royal (Gene Hackman) reading the actual letter, which confirms the information we've just learned.

This obsessive control, and reiteration, of information is a trademark of Wes Anderson style.

Check out this breakdown of how the screenplay for Moonrise Kingdom informs the visual style and execution of the finished film.

Screenplay lessons from Moonrise Kingdom

Wes Anderson films are also funny. The director understands that good visual comedy comes from compromising situations or contradictions.

I guess when I think about it, one of the things I like to dramatize, and what is sometimes funny, is someone coming unglued. I don't consider myself someone who is making the argument that I support these choices. I just think it can be funny.

In Anderson's films, often the darker the moments are in spirit, the funnier they can be. Here's an insightful breakdown by none other than Wes Anderson himself of a key scene in Grand Budapest:

Wes Anderson describes the anatomy of a scene in The Grand Budapest Hotel

Related Posts

- How to Write a Film and TV Script Outline →

- Your Ultimate Pre Production Checklist →

- How to Use Color in Film →

WES ANDERSON Characters

Who are Wes Anderson characters?

Wes Anderson characters have an absolutist world view, which is why they are so emotionally fragile and disappointed when the real world turns out differently than they had thought it to be.

Another trait shared by many Wes Anderson characters is that they are often walking contradictions. Children act like adults.

Adults act like children.

Bill Murray in The Royal Tenenbaums plays a psychologist with a depressed wife and serious insecurities, and Jason Schwartzman in Rushmore is a boy genius who is failing his classes.

Much of what makes Wes Anderson characters so remarkable is how he can craft characters who commonly act in ways most would deem inappropriate. These characters say and do awful things, and yet we are still pulling for them.

Why? Because we know they are human.

Wes Anderson characters are flawed both inside and out. They can be petulant, greedy, vengeful, vain, fastidious, controlling, manipulative, liberally perfumed. and yet still likable.

WES ANDERSON DIRECTING STYLE

How does Wes Anderson direct a film?

Wes Anderson films have a very interesting rhythm. The thing I most compare them to is a cinematic Rube Goldberg machine. Many of his scenes contain long tracking shots with rapid-fire action, almost as if characters moving through scenes are the little steel marbles.

Each action is activated with the culmination of a different action:

Zero’s job interview in The Grand Budapest

His editing transitions are very interesting, which is the trademark of any good director. You will find yourself moving through imagery quickly, but when you move onto the next scene the whole thing is completely static.

Using sharp transitions like this creates comedy, but also generates a bit of emotional inertia. We are still reacting to the images from before while applying our emotional knowledge to new and seemingly unrelated visuals. But they aren’t unrelated… this is by design.

Anderson also does cutaways that will, at times, break a scene in half. This is almost like a flashback, or a cutaway joke like a TV gag.

It suggests a profound trust in his viewer to have some level of visual sophistication. He trusts his audience to make those connections.

Here is a video of BTS footage from The Grand Budapest Hotel. This video gives a bit of insight into the Wes Anderson style in practice.

Wes Anderson directs scenes in The Grand Budapest Hotel

When watching BTS footage of Anderson, you quickly find that he doesn’t always work out the creative beats of the scene with actors. Instead, Anderson is giving line readings or adjusting the action of a character on an idiosyncratic level. He can’t help it, nor should he.

Line readings are a quick way to upset a professional actor, and they are generally considered a bit of a faux pas for directors. But Anderson doesn’t make films that offered by the studios, he brings projects that he created to producers and then makes them himself.

It makes sense that his desire for control extends to every line of dialogue. Gene Hackman, Bill Murray, Ralph Fiennes — these are not humble actors excited to get their first big role.

These are movie stars.

What the film looks like at the end is more important than making friends. That isn’t to say Anderson on set is a domineering taskmaster whipping actors like a pack of snow dogs. He gives everyone respect, never looks frazzled, and seems genuinely in love with making films.

Auteur Theory Made Practical

Explore directing techniques used by the greats

Create works like these iconic auteur directors. Explore practical directing tips you can immediately put into action on your next project.

EXPLORE Auteur Directors

Quentin Tarantino

Stylish & Theatrical

David Fincher

Ominous & Precise

Wes Anderson

Quirky & Colorful

Darren Aronofsky

Intense & technical

Steven Spielberg

Adventure Films

Zack Snyder

Stylish Noir Action

Wes Anderson Visuals

THE LOOK OF A STORYBOOK

WES ANDERSON cinematography style

Cinematography: Wes Anderson films

Wes Anderson is not a cinematographer; he's a writer and director.

Meet Robert Yeoman, one of the most prolific cinematographers working today. Yeoman has helped cement the visual template associated with Wes Anderson, so much so that Anderson has not worked with another cinematographer for any of his live-action feature films.

The Wes Anderson cinematography style starts with Robert Yeoman

Go and watch non-Anderson films that Robert Yeoman has shot. You'll see what he does differently, and the influence he has had on Anderson.

Anderson and Yeoman often present images in symmetrical, flat compositions. This furthers the "storybook motif" that Anderson creates with his visuals, letting viewers feel like they are moving through some sort of doll house world.

Wes Anderson cinematography style right down the middle

The imagery in Wes Anderson films can be light and fluffy, but it's presented in a direct, succinct, and precise manner. This gives it style and weight.

WES ANDERSON COLOR PALETTE

How does Wes Anderson use color?

Wes Anderson uses a lot of different colors and combinations in his films, and each scene has a distinct, premeditated assembly of colors. The Wes Anderson color palette is every bit as intentional as his directing style.

He and his crew often like to use muted browns, yellows, and reds:

Wes Anderson Color Palette in The Royal Tenenbaums

Color can elicit emotion from the audience, and the same colors can be connected to different emotions based on how you mix the colors, the surrounding imagery, and the general emotional tone of the scene.

In the case above, the browns and oranges play into the somber feel of the scene, and more importantly they are consistent with the look of the overall film. The colors in The Royal Tenenbaums make sense for the era, location, and characters. In short, the colors lend themselves to, and help define, the complete world of the film.

Wes Anderson on color choice in The Grand Budapest Hotel • Subscribe on YouTube

Other times the Wes Anderson color palette will call for bright, highly saturated colors. Look at any scene from The Grand Budapest Hotel.

Wes Anderson uses his color palette to split time periods in Grand Budapest. Each era’s saturated colors represent the mood at the time, specifically with regard to the hotel itself.

For more on color theory and using color palettes in film, we've got a FREE ebook on the subject.

Free downloadable bonus

FREE Download

How to Use Color in Film

Hue, saturation, brightness — the three elements of color that make all the difference. In this book, we'll explain the aesthetic qualities and psychology effects of using color in your images. Topics include color schemes like analogous and triadic colors and how color palettes can tell stories of their own.

WES ANDERSON fashion Style

What are Wes Anderson costumes?

One specific Jean-Luc Godard device that Wes Anderson uses in his films is what Godard referred to as “character uniforms.”

Similar to a cartoon character, the viewer is able to associate a consistent look with a specific character. The viewer forges a more significant relationship along with a set of expectations for each character.

Wes Anderson style on display with his "character uniforms"

Here is an example from Jean-Luc Godard’s Bande à Part. You can see a clear proto-Anderson approach to style taking shape:

In Bande à Part, Jean-Luc Godard uses "character uniforms" as well

There is a certain psychological comfort that comes from knowing what a character is supposed to look like. It doesn’t mean every character has to wear an official uniform, but the costume becomes a uniform over time. If that costume happens to be a traditional uniform, so be it.

Anderson's costume choices leave no room for imagination, mostly because Anderson has already taken up all the available real estate. He's being deliberate and removing all doubt.

If we are supposed to think of Willem Dafoe’s character as creepy and menacing, as in The Grand Budapest Hotel, he shows up wearing black leather and brass knuckles.

What if we are supposed to think of Willem Dafoe’s character differently, say. as a goofy sidekick? In The Life Aquatic, he shows up in short shorts and a goofy-looking beanie with a puffball on top.

Also, the crew members of the research vessel Belafonte wear the same red hats, but the characters tie the hats differently.

It is a small detail, some might even say a relentless detail, but it is yet another example of how three characters can ostensibly wear the same article of clothing. The manner in how they wear it says oodles.

Related Posts

- Master the Color Palette of Guillermo del Toro →

- Study the Color Palette of Denis Villeneuve →

- Build Your Film's Shot List and Storyboards →

WES ANDERSON font style

What is the Wes Anderson font?

Wes Anderson commonly uses the Futura and Helvetica fonts for his title cards. He has also been known to use Tilda and Didot as well. These fonts match the Wes Anderson style. They are simple, stark, and direct.

Even the Tilda font, which has a bit more flourish than the others, conveys an old-fashioned high-class sort of stability.

This consistency across his films either suggests that Anderson has a premeditated desire to maintain his auteur label, or he just really likes those fonts. a lot.

Wes Anderson font style explained

One of the really unique things about Wes Anderson and his style comes from the fact that we even notice his fonts.

This is because he constantly uses text throughout his films.

Why does Anderson make us read so much? Does he just want to flaunt his fonts? It goes deeper than that.

Anderson knows that forcing a viewer to read even small bits of information will forge a more significant bond with that information.

You often remember what you read. It's another way of conveying details about the story and the world. Text tickles a different part of the brain, and the Wes Anderson style fires on all cylinders.

Text allows him to be direct and succinct. Otherwise, Anderson would run the risk that his important information might be missed or ignored.

A well-designed and well-written title card can be a lot more effective than a clunky expository scene or a "Fred the Explainer" monologue.

Wes Anderson Filmography

List of wes anderson movies

Wes Anderson Films

List of Wes Anderson Movies

Wes Anderson films include shorts and feature films, but we'll keep our focus on feature films directed by Wes Anderson.

The French Dispatch (2021)

A love letter to journalists set in an outpost of an American newspaper in a fictional 20th-century French city that brings to life a collection of stories published in "The French Dispatch."

Isle of Dogs (2018)

When, by executive decree, all the canine pets of Megasaki City are exiled to a vast garbage-dump called Trash Island, 12-year-old Atari sets off alone in a miniature Junior-Turbo Prop and flies across the river in search of his bodyguard-dog, Spots. There, with the assistance of a pack of newly-found mongrel friends, he begins an epic journey that will decide the fate and future of the entire Prefecture.

The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014)

In the 1930s, the Grand Budapest Hotel is a popular European ski resort, presided over by concierge Gustave H. (Ralph Fiennes). Zero, a junior lobby boy, becomes Gustave's friend and protege. Gustave prides himself on providing first-class service to the hotel's guests, including satisfying the sexual needs of the many elderly women who stay there. When one of Gustave's lovers dies mysteriously, Gustave finds himself the recipient of a priceless painting and the chief suspect in her murder.

The Grand Budapest Hotel

Moonrise Kingdom (2012)

The year is 1965, and the residents of New Penzance, an island off the coast of New England, inhabit a community that seems untouched by some of the bad things going on in the rest of the world. Twelve-year-olds Sam (Jared Gilman) and Suzy (Kara Hayward) have fallen in love and decide to run away. But a violent storm is approaching the island, forcing a group of quirky adults (Bruce Willis, Edward Norton, Bill Murray) to mobilize a search party and find the youths before calamity strikes.

Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009)

After 12 years of bucolic bliss, Mr. Fox (George Clooney) breaks a promise to his wife (Meryl Streep) and raids the farms of their human neighbors, Boggis, Bunce and Bean. Giving in to his animal instincts endangers not only his marriage but also the lives of his family and their animal friends. When the farmers force Mr. Fox and company deep underground, he has to resort to his natural craftiness to rise above the opposition.

The Fantastic Mr. Fox

The Darjeeling Limited (2007)

Estranged brothers Francis (Owen Wilson), Peter (Adrien Brody) and Jack (Jason Schwartzman) reunite for a train trip across India. The siblings have not spoken in over a year, ever since their father passed away. Francis is recovering from a motorcycle accident, Peter cannot cope with his wife's pregnancy, and Jack cannot get over his ex-lover. The brothers fall into old patterns of behavior as Francis reveals the real reason for the reunion: to visit their mother in a Himalayan convent.

The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (2004)

Renowned oceanographer Steve Zissou (Bill Murray) has sworn vengeance upon the rare shark that devoured a member of his crew. In addition to his regular team, he is joined on his boat by Ned (Owen Wilson), a man who believes Zissou to be his father, and Jane (Cate Blanchett), a journalist pregnant by a married man. They travel the sea, all too often running into pirates and, perhaps more traumatically, various figures from Zissou's past, including his estranged wife, Eleanor (Anjelica Huston).

The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou Trailer

The Royal Tenenbaums (2001)

Royal Tenenbaum and his wife Etheline had three children and then they separated. All three children are extraordinary --- all geniuses. Virtually all memory of the brilliance of the young Tenenbaums was subsequently erased by two decades of betrayal, failure, and disaster. Most of this was generally considered to be their father's fault. "The Royal Tenenbaums" is the story of the family's sudden, unexpected reunion one recent winter.

Rushmore (1998)

When a beautiful first-grade teacher (Olivia Williams) arrives at a prep school, she soon attracts the attention of an ambitious teenager named Max (Jason Schwartzman), who quickly falls in love with her. Max turns to the father (Bill Murray) of two of his schoolmates for advice on how to woo the teacher. However, the situation soon gets complicated when Max's new friend becomes involved with her, setting the two pals against one another in a war for her attention.

Bottle Rocket (1996)

In Wes Anderson's first feature film, Anthony (Luke Wilson) has just been released from a mental hospital, only to find his wacky friend Dignan (Owen C. Wilson) determined to begin an outrageous crime spree. After recruiting their neighbor, Bob (Robert Musgrave), the team embarks on a road trip in search of Dignan's previous boss, Mr. Henry (James Caan). But the more they learn, the more they realize that they do not know the first thing about crime.

Best Wes Anderson Movies

The best Wes Anderson films

Which do you think are best Wes Anderson movies? How does his style work in those films compared to the ones you least prefer?

Here is our ranking of the best Wes Anderson movies:

- The Royal Tenenbaums

- The Grand Budapest Hotel

- The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou

- Rushmore

- Moonrise Kingdom

- The Darjeeling Limited

- Fantastic Mr. Fox

- Isle of Dogs

- Bottle Rocket

Everyone has a different feeling about which are the best Wes Anderson movies, but we always try to look at the films on a macro scale.

That's the power of film. we each have an individual connection to movies through our own personal experiences, but you can often find objective reasons to support a film as one of the best Wes Anderson movies.

WES ANDERSON Awards

Awards of note won by Wes Anderson

Wes Anderson has won fewer awards than one might think, but he has been nominated for many and watched as his team took home wins, which in my opinion makes it even more important to study his films.

Here is a list of the Wes Anderson awards:

Academy Awards

- Nominations - 7

- Wins - 0

Golden Globes

- Nominations - 2

- Wins - 0

BAFTA

- Nominations - 7

- Wins - 1 (Best Original Screenplay - The Grand Budapest Hotel)

UP NEXT

How to Use Color in Film

Now you understand more about Wes Anderson and his unique style. You've no doubt already started to realign the way you think about color in your films. It's time to gather tools to evoke specific emotions from your viewers. In our next post, you'll find out how to use color.

Develop your style and define your visuals by studying movie color palettes to figure out your own techniques.